Geometries of power: Harald Bluetooth's ring fortresses

The rise and fall of the only Viking citadels

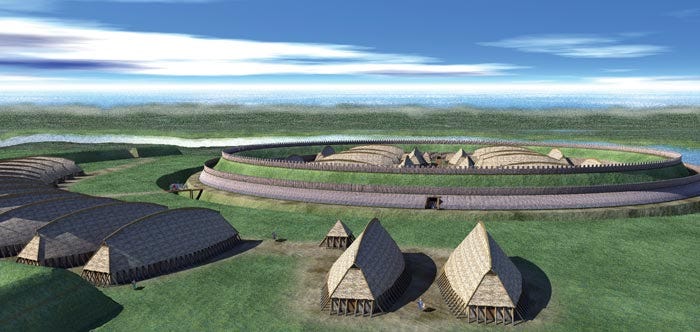

The Norse may not have built castles (though their Norman offshoot made history on that account), but picture this: five circular Viking “megadoughnuts” flung across Denmark like massive frisbees: Aggersborg up by the Limfjord, Fyrkat crouched beside the railway town of Hobro, Nonnebakken bossing the river bend at Odense, Trelleborg guarding Zealand, and Borgring hiding in the fields south of Copenhagen like a long-forgotten boss level. All five went up in a construction frenzy that lasted barely a decade, roughly 970–980 CE, each one parked slap-bang on a major land-or-sea highway and tweaked to exploit every river bend, fjord mouth and sandbar in sight.

In 2023, UNESCO finally looked over the shoulder of Danish archaeologists and said, “world heritage material.” No other large fortifications existed in Denmark in the rest of the Viking Age, from the end of the 700s up to the 1000s, except for the city walls in Hedeby, Ribe, and Aarhus. Chieftains and kings built large halls and farms, but not fortresses. So what led a Viking king to scatter gigantic turf doughnuts across his realm in the space of one royal heartbeat?

The fortress enigma

King Harald Bluetooth - the man whose nickname now pops up every time your earbuds sync - reigned circa 958–987 CE, and he’s famous for the Jelling Stones, Denmark’s granite “birth certificate” and the first place the word Danmǫrk shows up in stone. Yet Harald’s real flex wasn’t just carving runic shout-outs; it was stamping his authority onto the landscape itself. For sixty years after the last known ring fortress had been unearthed, scholars doubted they’d ever find another until Borgring slipped out of hiding in 2014, turning the academic chat room into Viking-age clickbait: was it really a fortress, or just a weird sheepfold?

Dating evidence soon showed that all five rings sprang up almost simultaneously, after Harald had ruled a dozen calm years and after he’d already splash-converted the realm to Christianity (963 CE). Weird timing for a sudden castle-building spree. And stranger still, once these doughnut-forts faded from use, Denmark never bothered with big new fortresses again until stone castles appeared centuries later. So what on Midgard was Harald doing?

Boot camp for the English invasion of Harald’s rebellious son? Nice try, but the tree-ring dates put the forts up decades before Sweyn Forkbeard sailed off to pester England.

National admin hubs? Plausible, Harald loved a good census, but why spend a fortune on earthworks only to abandon them within a generation?

Bluetooth vs. Forkbeard civil war? Dramatic, but a father-son slap-fight lasting ten years would have torn Denmark apart, and no saga whispers of it (he may have been exiled, though).

Defence against the Ottonian Empire? This was actually the prevailing theory for quite some time. Emperor Otto I bulled north in the 960s, and Otto II trashed the defensive wall called Danevirke in 974. Trouble is, the ring forts perch way up on Zealand, Funen and Skåne - great for harassing Baltic shipping, useless for stopping the armies of the Holy Empire on the Jutland border.

So, where does that leave us? With an enigma that tastes a bit like strategy, propaganda, and panic sprinkled together. Harald’s ring fortresses might have been less about blocking armies and more about broadcasting royal power at lightning speed. Imagine five colossal, geometrically perfect circles, each 120 metres across, four gates aligned to the cardinal points, barracks laid out with mathematical swagger, appearing overnight on the main trade routes. Message received: “Want to go viking against me? I, the Jelling king, can mobilise thousands, bend geometry to his will, and drop a military base in your backyard before you’ve finished brewing your ale.”

The result is unforgettable: five Viking Age “space stations” made of earth and timber, blazing like signal beacons of a kingdom in sudden overdrive. Their life was brief, their purpose still a bit shady, but their appeal? Pure saga fuel. Now here’s where the plot thickens -while the old theory that Harold Bluetooth’s ring fortresses were royal training camps or admin hubs has long made the rounds, a fresher, more tactical explanation might be closer to the truth: these strongholds were built not to launch Viking raids, but to protect Denmark from them. From other Vikings right at home.

While Emperor Otto II was stomping around Germany and threatening Denmark from the south, Bluetooth had to shift all his best warriors to the borderlands near the Danevirke. That left large swathes of Denmark, especially along the coasts and in the east, dangerously exposed. And who might seize that golden opportunity to strike? You guessed it: neighbouring fellows from Norway and Sweden. So what does a shrewd king do? He fortifies the realm not just at the point of attack, but all around it.

It’s defensive chess on a grand scale. Instead of concentrating his defences in Jutland, where the empire was pressing, Harold planted his ring fortresses like sentinels across the kingdom at key ports, river mouths, and crossroads - these weren’t frontline garrisons; they were safety nets, protecting local populations while the professional warriors were off swinging swords elsewhere. In other words, the fortresses weren’t full of fighters - they were empty so the fighters could fight.

This is more than theoretical - there’s a skaldic poem to back it up. Vellekla, a praise poem for the Norwegian Earl Haakon, tells how he responded to Bluetooth’s call to arms and rode south to help defend the Danevirke. This wasn’t just a local dust-up; it was a geopolitical crisis, a royal scramble for allies, and a desperate bid to hold the line. If the fighting elite were all massed at the southern frontier, then ring fortresses like Borgring were vital, sort of like castles you build when you can’t spare any knights.

The last circle

And Borgring, the final missing piece of the fortress puzzle, fits this theory like a key in a lock. Discovered in 2014 just south of Copenhagen near Køge, it had lain hidden for over a millennium. But archaeologists were hunting precisely because this theory predicted there should be a fortress on Denmark’s vulnerable eastern coast. And there it was. Excavations between 2016 and 2018 confirmed it: the same perfect geometry, same monumental gate structures, same eerie sense of quiet readiness. Archaeologists ran geophysical surveys, swept fields with metal detectors, and analysed soil chemistry across over 40 hectares to understand its footprint and use. Like the other ring forts, Borgring wasn’t some cobbled-together palisade. It was a carefully engineered, state-sanctioned defensive structure, part of a grand, realm-wide strategy.

Perhaps most impressively, these fortresses weren’t just reactive, they were quite visionary. They allowed Harold Bluetooth to do something no Danish king had done before: extend his authority across the entire realm. With each fortress, he anchored royal control, safeguarded vulnerable regions, and reallocated his military where it was most needed. The large buildings at Trelleborg, for example, hint that some forts doubled as winter quarters, supply hubs, or proto-communities. But their real genius lay in enabling flexibility: protecting civilians and infrastructure so warriors could be warriors somewhere else.

So yes, the rise of the Holy Roman Empire and its ambitions under the Ottos pushed Denmark into crisis - but it was the threat of opportunistic attacks from Norway and Sweden that truly shaped the map. The ring fortresses weren’t just military architecture. They were Bluetooth’s counterstrike in timber and turf, a decentralised yet unified defence system that let him fight in the south without losing his grip on the rest.

Borgring, the elusive fifth member of Denmark’s ring fortress network, was long buried in the Danish landscape, hiding in plain sight near the present-day town of Køge. It wasn't until the aerial photographs of the 1970s and a renewed wave of archaeological theory in the 2010s that its outline was definitively spotted, nestled in a natural corridor where a valley narrows to 200 metres and a ridge opens up across nearly a kilometre: perfect terrain for control and surveillance. Like its sibling fortresses -Trelleborg, Fyrkat, Aggersborg, and Nonnebakken - Borgring occupied dry, defensible ground near key roads, a shallow inlet, and a route into the river valley, though it sat just far enough inland to be protected from open-sea incursions.

Yet Borgring stands apart in several key respects. Its terrain posed greater challenges than other ring forts. The site required substantial pre-construction levelling, including the relocation of nearly 2,000 cubic metres of clay-rich soil, some of it containing older material like flint debitage and ancient pottery shards, to fill gullies and raise depressions. This extensive groundwork hints at an ambitious plan to impose geometric and symbolic order onto a chaotic landscape, a signature move of King Harald Bluetooth’s state-building efforts in the late 10th century.

Like other Trelleborg-type fortresses, Borgring was circular, measured out with the same system of standardised measurement known as the "Trelleborg foot" (~29.5 cm), and featured four cardinal gateways constructed with imposing timbers and roofed in planks. The inner courtyard was likely projected at 400 Trelleborg feet, or about 118 metres in diameter. The ramparts themselves were built in four identical quadrants and may have stood nearly 3 metres tall, possibly topped with a wooden palisade. This all fits the architectural blueprint seen at sites like Fyrkat and Trelleborg, reinforcing the idea that a central authority, likely King Harald himself, oversaw a kingdom-wide fortress construction project.

Despite this structural ambition, Borgring appears to have been abandoned before it reached completion. Unlike Trelleborg and Fyrkat, Borgring shows no evidence of internal streets, barracks, or wooden houses, and much of its rampart cladding was never finished. The southern and western segments of the rampart were barely preserved -suggesting erosion, incomplete construction, or both - and the gateway structures, though massive, show signs of intentional fire damage. In fact, three of the four gates were charred, and below one collapsed northern gateway, archaeologists found a delicate fragment of a rare type-7 box brooch from Gotland - perhaps dropped during the fire or left behind in haste.

Other findings were modest but meaningful: caches of well-crafted tools, an axe, several glass beads, iron ingots, and rare early glazed ceramics. One pit, sealed beneath the burned eastern gate, contained a hoard of iron tools, including a nail header, draw knife parts, a fire steel, and scrap iron, most of it likely sourced from bog iron in southern Sweden. The draw knife, however, stood out, made from high-grade iron from Central Europe, hinting at connections beyond the Baltic.

Radiocarbon dates and dendrochronological wiggle-matching from timber samples at the northern gate show that the trees were felled sometime after 930 CE, with the most likely construction window in the second half of the 10th century. This aligns Borgring with the known chronology of Bluetooth’s reign, and with the building campaigns of the other ring forts dated between 970 and 980 CE.

What’s fascinating about Borgring is that it seems to straddle the line between active use and symbolic presence. It may never have been fully operational as a fortress - no clear evidence exists of a stationed garrison or long-term habitation within the ring - but its sheer scale and strategic siting along a river crossing suggest it had real logistical and psychological importance. It’s possible that it served, like other Trelleborgs, not as a frontline military base, but as a safeguard for local populations and a royal claim staked boldly into the landscape.

Epilogue

Why wasn’t it finished? One plausible explanation lies in the internal politics of Bluetooth’s reign. By the mid-980s, his son, Svein Forkbeard, had turned against him. Chronicles from the late 11th century describe widespread unrest driven by two major sources of resentment: the burdensome labour demands of fortress construction and the forced Christianisation of Denmark. If the ring fortresses - massive, geometric, expensive - symbolised the king’s new order, then Borgring, as the last of them, may have been the tipping point. Its unfinished state and signs of destruction may reflect not neglect, but rebellion: a deliberate halting of royal authority by fire.

This would explain the absence of internal buildings and full cladding, as well as the fire damage to its gates. It also repositions Borgring not as a failed project, but as the dramatic endpoint of Harald’s great fortress-building scheme - a campaign that consolidated the realm while possibly also sparking the internal opposition that would lead to the king’s downfall.

Viewed in this light, the Trelleborg fortresses, Borgring included, were not just military installations. Their identical measurements, deliberate geometry, and prominent siting made them architectural statements: assertions of central power, unity, and order imposed from above. As monuments, they radiated political control over the landscape and visualised the reach of a newly unified Danish monarchy. But they also came at a cost - literally, in labour and resources, and figuratively, in the political backlash they provoked.

In the end, Borgring isn’t just a ring of earth and timber - it’s a dramatic full stop at the end of Bluetooth’s grand fortress-building saga. Borgring might not have seen many warriors bunking down for winter, but it saw the high tide of royal ambition - and the first cracks in the walls. A symbol of control that may have overreached, a monument to order that ended in fire. Perhaps the most dramatic unfinished project of the Viking Age.

Further reading:

J. Christensen et al., “Borgring. Uncovering the strategy for a Viking Age ring fortress in Denmark”, in the Danish Journal of Archaeology 10, pp. 1-22

Fascinating - is this the only place where this kind of defensive structure exists, or are their similar templates elsewhere? what a foresighted king, protecting the populace with these defensive villages.

Really fascinating. I basically know nothing about this period/region but this has intrigued me! The aerial shots showing the “megadoughnut” are spectacular- what a change in perspective can do.