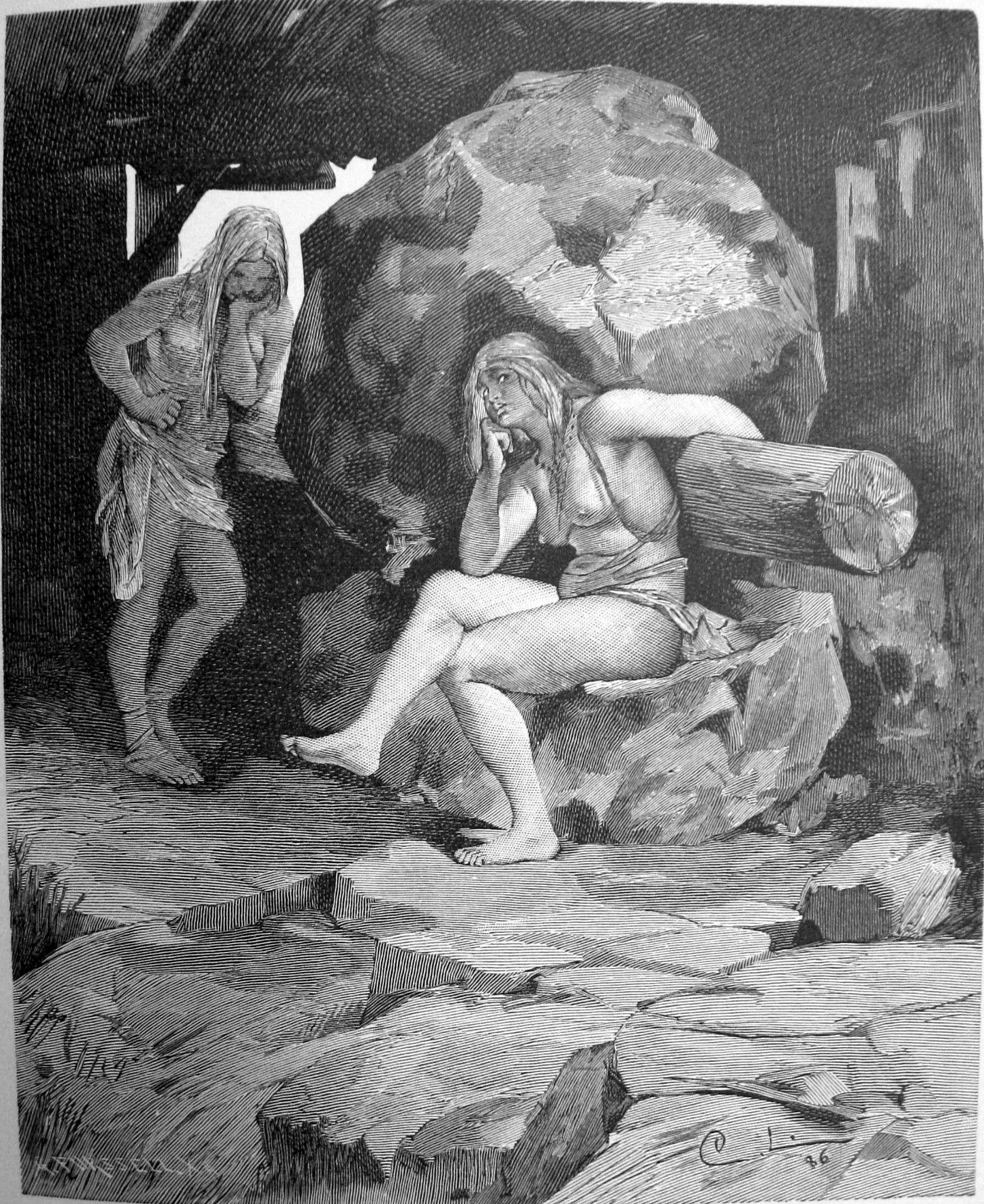

Once upon a myth, the Danish king Frodi (not a hobbit) made a questionable decision: he acquired two enslaved women, Fenia and Menia, from Sweden. Little did he know they were no ordinary captives, but towering descendants of mountain giants. He brought them back not just to toil, but to operate Grotti, a magical millstone with the power to grind out anything the heart desired: gold, peace, happiness, you name it. Sounds idyllic, right? Except Frodi, blinded by his lust for effortless riches like most capitalist profiteers nowadays, demanded nonstop production. No breaks. No mercy. Just endless grinding.

This compelling story is the topic of the Norse poem Grottasöngr. The girls are taken straight to the mill to start working: the king does not even mention rest before hearing the slave-women’s tune. They accordingly set to work: the sound of industry rings out, as they adjust the machine, and the king again orders them to work. The milling, accompanied by the girls’ singing, continues until Frodi’s household is asleep, and the flour begins to emerge. Needless to say, things did not go well from here.

Fortunately for Fenia and Menia, unlike many of us stuck in the hyper-productive, burnout-inducing work culture, they weren’t helpless. They had powers of their own. What happens when you force ancient, magical beings into unpaid overtime? Vengeance. The kind that grinds kingdoms into dust.

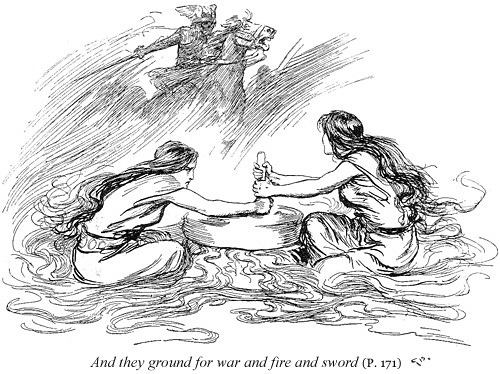

The girls, who once played with boulders in the mountains (some of which became the very millstones they were now chained to), took matters into their own crafty hands. The maidens used to engage in battles, toppling and upholding kings as they chose. With no explanation as to how it happened, they were then brought into captivity and misery to the court, where these erstwhile warmongers were ironically reduced to turning the mill. Fenia takes over the song: they will not rest their hands, she says, before Frodi deems that enough milling is done. The irony of her statement is then revealed: it is spear-shafts that hands shall grasp. Instead of gold and grain, they ground out a vengeful army. According to Snorri Sturluson, this force belonged to Mysing, a fearsome sea-king who promptly stormed Frodi’s kingdom. And that was that for the king.

But the tale doesn’t end there. Mysing, evidently no better a boss than Frodi, hauled the sisters onto his ship and commanded them to grind salt. They delivered so effectively that the ship was overwhelmed and sank beneath the weight of their production. And that, as the myth goes, is why the sea is salty.

These stone-grinding sisters weren’t just mythic labourers, they were battle-hardened, valkyrie-like figures with the power to shift the fates of kings. Their descent from the giants gave them both strength and a tragic destiny: from high-stakes military manoeuvring to being enslaved for endless production. This ancient tale still speaks volumes about power, labour, and what happens when you push the wrong women too far.

Frodi - kings of legend

The figure of Frodi (Fróði in Old Norse) straddles the blurry line between history and myth. In Beowulf, Froda appears as a Heathobard king, likely echoing a real 5th-century leader. But in Norse tradition, Frodi becomes something else entirely: a legendary Danish monarch, sometimes wise and peace-bringing, sometimes tyrannical and doomed.

Rather than one man, Frodi becomes a dynastic archetype. Norse sources like Skjöldunga saga and Saxo Grammaticus present multiple Frodis - five in Saxo’s case -each embodying a different fate. The first, Frodo I, presides over a miraculous era of peace (linked in Christian sources to the birth of Christ), but dies violently at the hands of the pirate Mysing. Later Frodis meet stranger ends: one is impaled by a stag, another kills his brother only to spark an endless cycle of fraternal revenge.

This shifting figure reflects more than confusion, it shows how myth evolves to express different truths about kingship. Snorri Sturluson tries to clarify things, aligning the golden-age Frodi with Frodo I and ignoring the harsher Heathobard version altogether.

Yet in poems like Grottasöngr, Frodi’s reign is no paradise. Here, he is a cruel overlord, grinding wealth from enslaved giantesses, until their rage brings his doom. This narrative mirrors the fall from divine harmony into human exploitation, echoing Völuspá’s lost golden age. Even more striking is the way Frodi blurs into Freyr, the fertility god. In Ynglinga saga, it’s the god Freyr, not Frodi, who brings peace and plenty. After Freyr’s death, his followers keep his corpse on display, pretending he’s alive to maintain prosperity. Saxo mirrors this with Frodo III, paraded post-mortem to keep the illusion of stability.

In the end, Frodi is not just a name, he’s a mythic cipher for how power, peace, and legitimacy are remembered, manipulated, and mythologised. Whether as a wise ruler, a brutal tyrant, or a symbol of divine order lost, Frodi tells us more about the societies that told his story than about any historical king.

Cosmic wheels

The tale of Fenia and Menia seems at first glance a grim little story about forced labour and revenge. But beneath the surface, something stranger stirs: echoes of cosmic wheels turning, golden ages lost and found, and primordial beings ground to dust beneath millstones. This is myth as machinery, and the giantesses are not merely cogs in it, they are its grim operators.

Their story may resonate with a curious episode in the poem Völuspá stanza 8, where three giant maidens arrive unbidden during the gods' golden age. The Æsir gods are joyfully playing a kind of divine board game (töflur, likely akin to chess), when the giantesses break in. The poem doesn't spell out what happens, but it seems the giants win, or at least, their arrival signals the end of the fun. The golden game pieces vanish until they resurface in Völuspá 58, heralding a reborn world. These mysterious women, then, are harbingers of decline, yet also perhaps of necessary transformation.

In Grottasöngr, the tone is darker. Fenia and Menia are no longer distant omens but central figures in the downfall of a kingdom. Once innocent stone-players in their ancestral homeland, they are captured and forced by King Fróði to grind out wealth and peace on Grotti’s massive quern. Their enslavement feels random, meaningless, until they begin to speak. Slowly, they reframe their past: they weren’t just dragged into history; they saw it coming. Their suffering becomes something more than misfortune. It becomes a kind of kenosis, a divine self-emptying, a purposeful descent that ends with vengeance and, crucially, liberation. They don’t just break the mill; they break the king.

This theme - superhuman figures forced into servitude, only to turn the tables - is a recurring one in Norse myth. Take Vǫlundarkviða, where the master-smith Völund (Wayland) is crippled and imprisoned by King Nidud, who wants him to forge golden treasures. Like Fenia and Menia, Völundr bides his time, crafts with grim skill, and eventually unleashes devastating revenge. Gold flows, but it flows from pain, and it always ends in blood.

This idea of a wonder-working mill crops up in other traditions, too. In many folktales, magic mills churn out endless goods like salt, gold, grain on their own. But Grotti isn't like that. It’s only as magical as the muscle behind it. No grinding without the giantesses. And that makes it more myth than machine.

A particularly striking parallel comes from Finnish mythology: the sampo. According to the Kalevala, this enigmatic object - part mill, part pillar, part cosmic engine - is forged by the smith Ilmarinen as part of a murky bargain with the Mistress of Pohjola. Once created, it delivers prosperity to Pohjola… until it’s stolen, broken, or lost. The sampo doesn’t just make wealth, it makes destiny. It may even represent the world pillar itself, capped by the "kirjokansi", the speckled lid of the heavens. Some link this to the North Star, imagined as the “nail” pinning the sky in place, around which the heavens grind in an eternal rotation. That rotation, in Finnish folk terms, was a kind of grinding: sammasjauho, pillar-milling. And suddenly, the cosmic quern doesn't seem so far from Grotti after all.

Granted, Grotti doesn’t explicitly grind the heavens. It lacks the explicit world-pillar imagery of the sampo. But Norse myth isn’t done with grinding. In the poem Vafþrúðnismál stanza 35, we encounter Bergelmir, last of the primordial giants, whose strange fate involves being placed in a lúðr, a “mill-crib,” if we take the word literally. Some editors squirm at the idea, but the implication seems to be that he was ground, just like barley. And barley, fittingly, is everywhere in this mythic grainstorm: In the poem Lokasenna stanza 44, Loki mocks Byggvir (whose name literally comes from “barley”) for clucking under the quernstones, a servile creature caught in endless milling.

The strange genealogy of the giants Aurgelmir, Þrúðgelmir, or Bergelmir has also been re-read in agricultural terms. Aurgelmir is born from aurr, fertile mud, and his monstrous six-headed grandson? Not a freak of nature, but an emmer wheat ear. Giants perhaps could be seen not as chaos-bringers but as cosmic crops - sown, grown, harvested.

In this light, Grottasöngr isn’t just a tale of revenge. It’s a mythic meditation on transformation, sacrifice, and cosmic machinery. The grinding mill is not just a source of wealth, it is the world’s stomach, endlessly churning matter into meaning. Fenia and Menia, like the wheat they grind, are broken down to build something new. Their suffering isn’t senseless. It’s mythic.

And the wheel keeps turning.

Read the poem here: Grottasöngr

Fascinating stuff Irina, thank you. I think I know where my dreams will take me tonight 🤔😳☺️🤗

Ooo i didnt know this . Thank you