“I’ve been contending with Odin in words of wisdom, you’ll always be the wisest of beings”. (The Lay of Vafthrudnir, stanza 55, transl. Larrington 2014).

Odin features heavily in accounts of Norse mythology, ranging from expert scholarship to popular culture, commonly designated as the mightiest of the Æsir (the main family of gods). He holds the position of overall superiority in a hierarchical pantheon, boasts the title of Alföðr (All-Father, though in one myth Heimdall spawned the social classes), he "lives for all ages, and rules over his entire state and decides all things, great and small", is a wise and cunning magician, can speak to the dead, masters the art of poetry and recruits the best warriors for his Valhöll (literally the hall of the dead) to prepare for the the encounter with the only deity he ultimately cannot defeat: fate. - Björn, you won a great victory today! - Dedicated to you, All-Father! - Great, now you get to die and assist me at Ragnarök. - Brilliant. Wait, what? But I won. - A seat in the golden hall on my benches of chainmail. - But now I can rule this kingdom. - There is free mead for all eternity. - Alright, let’s go. I think we can all agree that the Valhöll story makes for compelling militaristic propaganda. This Odin, massively skilled in war and magic, the “High-One” is to a great extent a product of the remaining texts dealing with mythology, the Poetic Edda and Snorri’s Edda, Icelandic texts from the 1200s.

Ironically, in Iceland, Odin occupies a less than respectable place in the memory of people writing about their ancestors in the family sagas. How much the written sources tell you what Hoskuld and Gunnhild were doing near their hearth in the longhouse after a day of gathering hay remains very questionable. If you were a farmer trying to settle in an unhospitable environment, threatened by crop failure, losing your sheep in a storm or angry neighbours claiming your meadow, maybe Odin with his selfish and irreverent demeanour would not have been your first option for a deity. A lad like Thor, however, might indeed make your life bearable. After all, he is the giant-slayer, the protector of mankind par excellence, the one who battles the world serpent Jormungand and even smashes its head before Ragnarök, according to some traditions (the poem of Bragi Boddason). In the Landnámabók (Book of Settlements), a record of orally preserved memories about the settlement of the island from the start of the 12th century, only one reference is made to Odin and that in a context of battle - a poem by Helgi Ólafsson who calls him “ruler of the gallows” to whom a warrior is sacrificed. Nothing about worship, though.

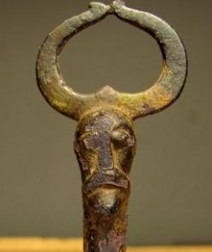

Unlike Thor, who clearly appears to be worshipped by some of the settlers. Thorolf Mostrarskegg “made many sacrifices and believed in Thor” (blótmaðr mikill ok trúði á Þór), had his image carved on his high-seat pillars (öndvegissúlur) and promised to dedicate his new lands to the god. His son also asks Thor to lead the way after a sacrifice, while another bloke called Kráku-Hreidar carved an image of Thor on his prow. Everyone’s favourite, though, should be Helgi the Lean, who “believed in Christ but made pledges to Thor for sea voyages and in difficult times (trúði á Krist, en hét á Þór til sjófara og harðræða). Whatever works for you, Helgi. Koll called on Thor for help in a storm, Ásbjörn consecrated his settlement to Thor, and Thórhaddr from Trondheim, described as a “priest” (the term goði indicates both secular and spiritual power) brought both his pillars and the earth beneath them. These accounts suggest a range of activities related to Thor and a connection to nature - sea, storms, and trees via the wooden pillars known from much earlier sources. Furthermore, if you have a look at the index of place names from the Íslenzk fornrit edition of the Book of Settlements and the Book of Icelanders, you’re going to be struggling with over ten pages.

Chieftains, warriors and poets loved Odin, so mainly the elites. We often find Odin in genealogies of famous families such as the famous Scyldings of Denmark, the Wuffingas of East Anglia. Cerdic of the Gewisse, who ruled Wessex in Southern England, also claimed lineage from Woden/Odin. The god is no doubt at least as old as the migration period (5th century), as confirmed by a recently discovered bracteate in Vindelev, Denmark. But that doesn’t mean he was worshipped everywhere or by everyone. Even in terms of divine origins, the legendary Ynglingar dynasty of Swedish and Norwegian kings claims an origin from Yngvi-Freyr. Freyr is also mentioned more often than Odin in the Icelanders’ stories. Thorsteinn and Freysteinn do not have an Odensteinn counterpart - the range of people’s names could say something about their ancestors’ beliefs. Place names in Iceland denoting key spots in the landscape bear the name of our angry redhead: Þórshöfn (harbour), Þórsnes (headland), Þórsmörk (woods), Þórsá (river), Þórseyri (sandbank). Unlike in Denmark and Sweden, Odin does not seem to have been remembered in any of the places named in Iceland. Finding a spear and horse in someone’s grave does not necessarily mean they were trying to mimic Odin’s spear Gungnir and the eight-legged beast Sleipnir.

“I make an oath on the ring, a legal oath; may Freyr, Njörðr, and the almighty Ás help me” - says the law of Ulfljöt, who travelled to Norway to learn legal history, according to the Book of Settlements. Was the almighty god Odin? Maybe. To be fair, he does appear in other triads: In the poem about creation and apocalypse Völuspá, he is involved in shaping the first humans alongside Hoenir and Lodurr (possibly Loki), whereas the Saga of Hákon the Good describes the heathen yule feast, where the Christian king was also expected to participate: first a toast to Odin (Óðins full), for the king and victory, and then others to Frey and Njörd (Freys full and Njarðar full) for árs ok friðar (good harvests and peace). The writings of Snorri often present Odin as the highest and mightiest - in Ynglinga saga, we can find a long list of his attributes, especially from the sphere of battle sorcery like blinding or numbing enemies, the sort of thing you’d normally stumble upon in Heroes of Might and Magic. He’s also credited with bringing the custom of cremation following the old rites, yet a few pages later, we find Freyr in a burial mound. Consistency was not Snorri’s strongest asset.

As a medieval Christian scholar following learnt traditions, Snorri aspired to offer a coherent and unified view of the pagan past in the Prose Edda. But pre-Christian religions don’t work like that - they are much more versatile and focus on practice and ritual rather than coherent mythologies applicable in all communities. In short, the corpus of evidence for Iceland does not suggest that Odin was widely worshipped by a majority of the settlers here. Kristni saga, a story that details the power struggle between pagans and Christians, does not turn Odin into the champion of resistance but generally mentions the Æsir having power over nature, which hinders the missionaries’ work. The wrath of the gods in general is given as an explanation for the volcanic eruption occurring near Thingvellir during discussions about conversion in the year 1000. The poet Thorbjörn dísarskáld, writing around the time, invokes the powers of Thor for protection, including against bickering missionaries:

“There was a clang on Keila’s crown, you broke all of Kjallandi, you had already killed Lútr and Leiði, you caused Búseyra to bleed, you bring Hengjankjǫpta to a halt, Hyrrokkin had died previously, yet the swarthy Svívǫr was [even] earlier deprived of life” (transl. skaldic.org). Almost nothing is known of these giantesses and giants -Hyrrokkin is a tad more famous for having rolled the boat for the funeral of Baldur, but she causes an earthquake, which angers Thor, who wants to kill her, but the others decide to spare her. A similar poem was written by one Vetrlidi, who seems to have been killed by a missionary. Thor as a pagan god would have caused more trouble to the new religion, because Thor, like Jesus, was a protector of the common folk. For all his lack of magical abilities and clumsiness - check out The Lay of Harbard for a delicious verbal duel between Odin and Thor - he compensated with his role as defender. The archaeological abundance of Mjölnirs (hammers) confirms his popularity.

Most poets (skalds) would have loved Odin, nevertheless. With immense skulduggery, Odin infiltrates the realm of the giant Suttung, seduces his daughter shapeshifting as an eagle, and drinks all three vats of “Kvasir’s blood” - the inspiring liquid resulting from mixing mead with the blood of the wise being concocted from the spittle of the two warring families of gods. Again, the clear-cut distinction between Vanir and Aesir might have been clear only in Snorri’s mind and not even there. Such a compelling myth would provide a template for the relationship between Odin and human poets. Mind you, if you consume the mead from the eagle’s droppings, you’ll be a mediocre poet at best. Odin's cult in Iceland might have been limited primarily to a community of poets who would have had reasons to learn and preserve Odin-related poems like The lay of Grimnir (Grímnismál), The Lay of Vafthrudnir (Vafthrúdnismál), The Prophecy of the Seeress (Völuspá), and much of The Sayings of the High One (Hávamál) as background knowledge for their poetic art, possibly seeking favour from foreign, largely Norwegian kings.

If you read Egil’s saga, you’ll encounter the poem Sonatorrek, written by Egil to lament the death of two of his sons. It’s just one of his artistic displays; on a different occasion, he makes up a praise poem for Eric Bloodaxe to save his life from his wrath. The poem Sonatorrek, written in old age, reveals Egil’s complicated relationship with Odin: he turns against the god for breaking their friendship, but in the end, he acknowledges that he did receive an extraordinary compensation in the gift of poetry. Yes Egil, you should be grateful, your lads did not even die in battle to serve in Valhöll, yet here you are writing in fornyrðislag (the epic metre). Metrical forms and metaphors (kenningar) in Old Norse are so convoluted that only a cunning and malicious being like Odin could have invented them. Kings would have a particular interest in using Odin to legitimize their power. Take Hákon of Lade, for example. In a backlash against Christianity, he enabled all of Thor’s temples but claimed descent from Odin. The poets conjure an image of Hákon as a majestic leader in battle but also bringer of good harvests, in the latter role more related to Freyr: “destroyer of princes” and “lord of Frodi’s storm”, according to his court poet Einar skálaglam.

What does this whole story tell us? Old Norse mythology should not be viewed as a uniform system across Scandinavia, and regional differences likely existed. Evidence from western and northern Norway, the origin of many Icelandic settlers, also shows a comparative scarcity of Odin place-names and a commonness of Thor place-names. Irish annals refer to Norwegian invaders as belonging to "muinter Tomair" (the tribe of Thorr), further highlighting Thor's perceived importance. Despite questions about his widespread worship in Iceland, Odin plays significant roles in various myths. For instance, he is the father of Váli, conceived through magic to avenge Baldr's death. This highlights his capacity for strategic action within the divine realm. Odin matches the archetype of the wise and cunning magician, but, like other mythological figures, is a complex character who doesn't fit neatly into a simple role. After the conversion to Christianity, the image of Odin underwent further transformation. One aspect of Odin may have blended with the figure of Christ (due to shared themes of self-sacrifice and connections to the afterlife, although Odin does it for very selfish reasons, to gain knowledge only for himself), while another became demonized in folklore.

Our understanding of Odin is shaped by the mediated representations of myth that have survived, each influenced by its context and purpose. In some legendary sagas, Odin is either a troublemaker, the remnant of a distant pagan memory, or offers to assist only to be dismissed, like Hrólf Kraki does in the saga. He and his champions were aware of his victory-bringing capabilities, yet turned him down. Unlike Thor, Odin did not evolve into a folk hero figure and cannot be played by Chris Hemsworth.

I had no idea! I thought Odin was the Big Dog. The All-Father. Zeus. Very enlightening.

The Romans identified Odin with Mercury and Thor with Jupiter.