Runic “social media” in medieval Norway

What were people in 13th century Bergen writing in runes?

When you think of runes, you probably picture towering runestones scattered across the Scandinavian landscape—silent witnesses to the lives and deeds of those who lived in the Iron and Viking Age. But here’s the thing: runestones weren’t the everyday choice for rune carving. They were expensive, required a skilled stonecutter, and were meant to last for centuries.

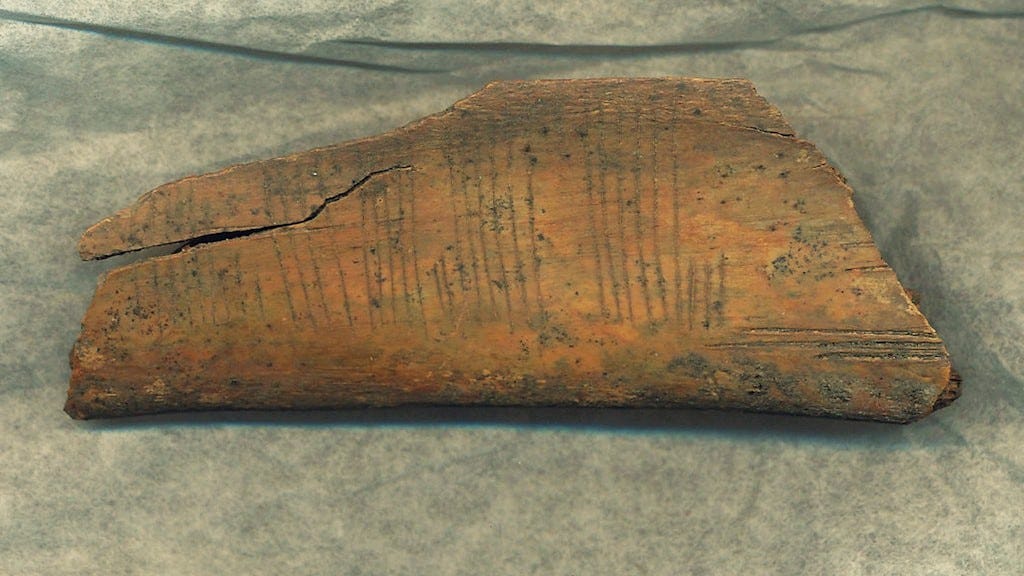

Most people, however, carved runes on materials like wood or bone—far more common but far less likely to survive the passage of time. These rune sticks give us a rare glimpse into the daily lives of medieval people: messages, notes, love spells, insults, and even magical charms! While runestones served as grand monuments of remembrance, these more humble runes captured something just as fascinating—snapshots of real, everyday moments. And though the Viking Age ended, the tradition of rune carving lived on, evolving in surprising ways.

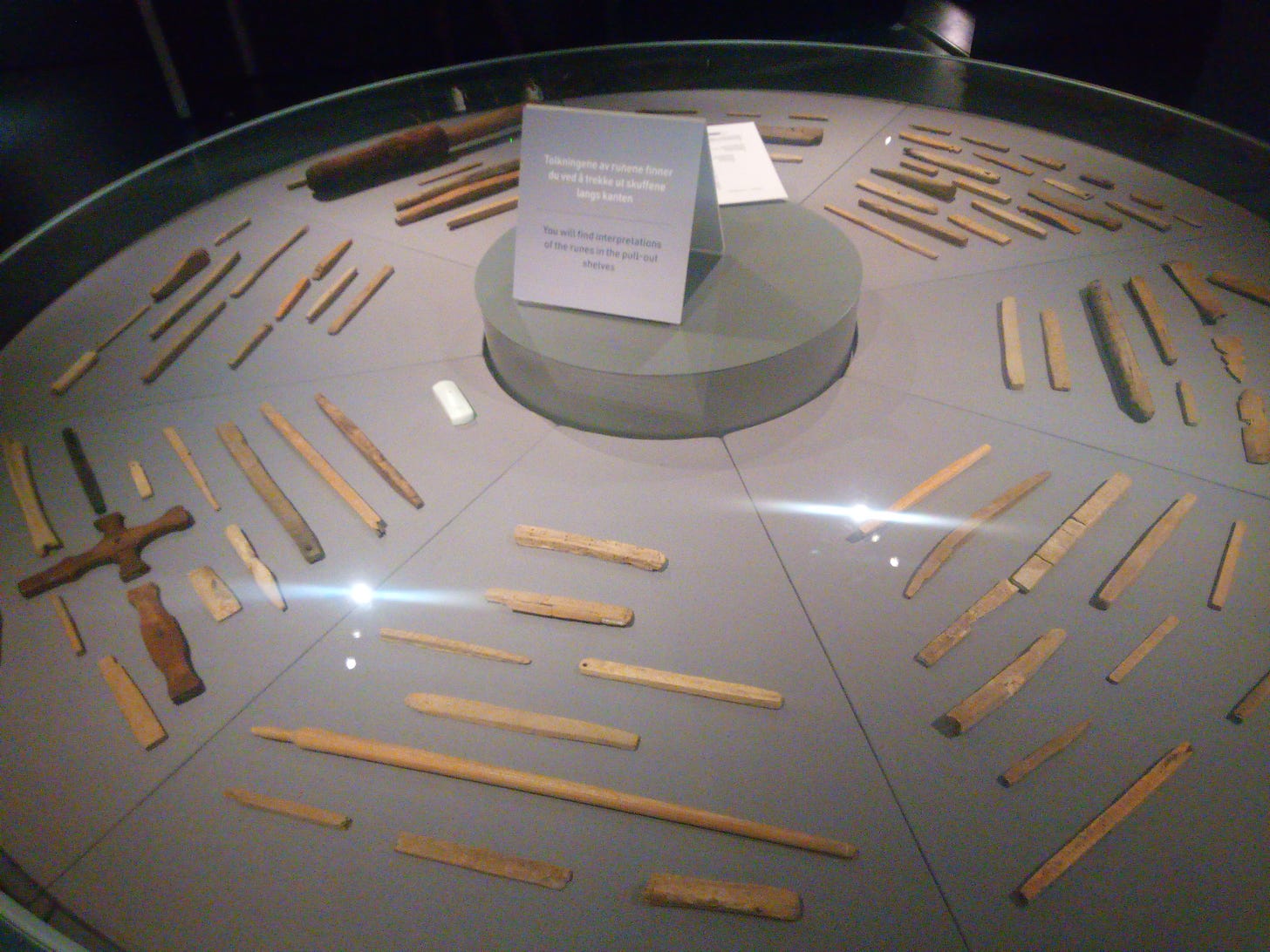

So, how exactly did medieval people use these runes? The most important collection of rune sticks comes from the historic harbour district Bryggen in Bergen, Norway, and was discovered in 1955. It contains about 650 medieval rune sticks from the 12th-14th century, with many kinds of usages. The most intriguing ones, of course, are those with a hint of mysticism. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

Pagan scribbles

We do have some late pagan references: an invocation of pagan deities is surprising at this date as Norway was supposedly fully Christian by the twelfth century, may have no supernatural function, but rather simply represent the recording of a traditional literary quotation or blessing. After all, fragments of identifiable Norse poetry recur on several other Norwegian rune-inscribed sticks. This particular text is unparalleled and is written in an unusual poetic metre known as galdralag, literally ‘the incantation metre’. Possibly, then, it originated as some form of charm.

Heill sé þú ok í hugum góðum! Þórr þik þiggi, Óðinn þik eigi.

“Hail to you and (be) in good spirits! May Thor receive you, may Odin own you.”

The idea of Odin’s ownership of his fallen warriors recurs throughout Old Norse literature and is made explicit in the prose Tale of Styrbjorn (Styrbjarnar þáttr svíakappa) in the Icelandic collection of tales known as Flateyjarbók. This tale records that, prior to the Battle of Fyrisvellir in the year 960, the Swedish king Erik, after sacrificing to Odin, cast a stick over the opposing army while making the allegedly traditional battle cry: “Odin owns you all” This inscription from Bergen may thus be a funerary charm appealing to the gods to receive a corpse. However, the opening line, wishing good health and spirits, does not seem to align with this view. Alternatively, it could just be a greeting, as the formula “hail to you in good spirits” is attested elsewhere in mythological poetry.

“The Lord of the Noose” Odin is invoked on yet another rune-stick from Bergen, and once more, the reference seems surprising at first given the late date of the object (probably between 1375 and 1400, the end of the runic period:

“I exhort you, Odin, with heathendom, greatest of fiends; assent to this: tell me the name of the man who stole; for Christendom; tell me now your misdeed. One I revile, the second I revile; tell me, Odin! Now is conjured up and lots of devilish messengers with all heathendom. Now you shall get for me the name of he who stole. A(men).”

This is what we deem “judicial prayer”, where the stolen item, though absent, was dedicated to a god who was then exhorted to pursue the wrongdoer to retrieve the item and then punish the thief. Although a capricious and untrustworthy god, Odin was renowned for giving wise counsel to his champions. He was also a practitioner of the mysterious form of sorcery known as seiðr, used to reveal hidden truths among many other things.

On another rune-stick from Bergen, we can find a reference to Norse mythic beings that are not gods. This late charm dates from about the year 1335 and invokes elves, trolls, ogres and valkyries, all familiar figures from Norse myth and folklore.

“I cut cure-runes; I cut help-runes; once against the elves, twice against the trolls, thrice against the ogres . . . ‘Against the harmful skag-valkyrie, so that she never shall, though she ever would – evil woman! – injure your life. ‘I send you, I look at you, wolfish perversion and unbearable desire. May distress descend on you and joluns wrath. Never shall you sit, never shall you sleep . . . ‘(that you) love me as yourself.’ Beirist (?) rubus rabus et arantabus laus abus rosa gaua . . .”

The runes on the Norwegian stick are carved against creatures of increasing malevolence, i.e. elves, trolls and ogres, moreover these were deliberately chosen to follow the alliteration of ‘once, twice, thrice’. A similarly threefold injunction against supernatural beings, but in a descending hierarchical order, is also found in the compilation of Old English medical charms known as Lacnunga. Although the precise meaning is unclear, the fiendish nature of the skag-valkyrie is paramount in the Bergen charm. Bloodthirsty valkyries such as Thrud and Gunn are also mentioned in the poetry of the Karlevi and Rök rune-stones from Sweden, and amulets in the shape of valkyries (or at least some feminine mythical figures) have been identified in Viking-Age Scandinavian graves. To suspect active paganism from the sources would be far-fetched, but there are clear traces of pagan remnants morphing into folklore.

Spicy scribbles

Scandinavia’s runic texts aren’t all solemn inscriptions of epic deeds—some are essentially the mediaeval equivalent of bathroom graffiti or the love-struck scribbles you’d find carved into trees and park benches. A few might even be ancient pick-up lines or magical love charms.

For example, Ingibjörg unni mér þá er ek var i Stafangri, “Ingibjorg loved me when I was in Stavanger”. This one reads less like profound wisdom and more like a cheeky brag— medieval locker-room talk. You can also read much nastier Bergen rune-sticks: Smiðr sarð Vigdísi af Snældubeinum, “Smith shagged Vigdis of the Snelde-legs.” These everyday scribbles stand in stark contrast to the more poetic or magical inscriptions—no grand spells or elegant verses here, just plain old chit-chat.

Some inscriptions could be downright vulgar, such as those using the old word for vagina, fuð, also the first three letters of the runic alphabet. The orthographic coincidence may explain the relatively frequent appearance of fuð in contexts which suggest it could have been used as an amulet charm word, much like the word lauk ‘leek’, a phallic herb. On this stick from Bergen, we find the following scribbling with no magical connotation: “Jon Silky-vagina owns me, and Guthorm Vagina-licker carved me, and Jon Vagina-swelling reads me.” Blushing already? Mediaeval people loved obscenity and did not refrain from showing it. A further inscription on a piece of wood from Bergen is similarly blunt, with a text that states: Rannveig rauðu skaltu serða. Þat sé meira enn mannsreðr ok minna enn hestreðr, ‘You will shag Rannveig the red. It will be bigger than a man’s prick and smaller than a horse’s prick.’ To judge the function of the inscription correctly, we would need to know more about the context, such as whether Rannveig owned the bone or had given it to a lover. But the mention of horse’s pricks does not seem too far removed from the world of vaginas, futharks, leeks or even fertility charms.

A rune-stick from Bergen contains a complete futhark row plus the words Ást mín, kyss mik!, ‘My beloved, kiss me!’ Sometimes, carvers used runes to try to effect their desires rather than spell them out for private or public amusement - amatory inscriptions addressed directly to a lover. Many of the direct appeals for love even demand some kind of reciprocity. “(Think) of me, I think of you!” says a stick. A counting-staff from Bergen even addresses a certain Gunnhild with the words Unn þú mér, ann ek þér, Gunnhildr! Kyss mik, kann ek þik!, “Love me, I love you, Gunnhild! Kiss me, I know you (well)!” Odin himself is well versed in such magic craft, boasting of his conquests in the Song of Harbard, gleefully recounting how he used “mighty love-spells” on witches to seduce them from their men.

Unrequited desire or unhappy love affairs are also features of Norse inscriptions, again, something we have in common. In one inscription, on a stick from Bergen dating to about the year 1300, after recording a routine transaction, the unhappy runic scribe complains in verse: “Wise Var of wire makes (me) sit unhappy. Eir of mackerels’ ground takes often and much sleep from me.” Var was a Norse goddess of marriage and oaths, and the metaphor “wise goddess of wire (i.e. filigree)” means “wise bejewelled woman”, so this line essentially means “women make me miserable”. The other figure, Eir, may be related to healing and “fish-ground” is probably a further metaphor for gold. Thus, the “goddess of the gold” appears to mean adorned as well. The whole line is perhaps to be understood as “women often take a lot of sleep from me”. Other inscriptions even speak of a lover’s dilemma when he is in love with another man’s wife. Or even expressions of spite and jealousy: “Evil take the man who has such a woman” is carved on a wood beater. Poetic fragments in Latin are also known, some even imitating songs from Carmina Burana.

Magic scribbles

Healing spells and leechcraft are also common in Old Germanic literature e.g. this rune-stick from Bergen: Bót haf þú, velkom(inn), “You shall have a cure, welcome.” Another stick inscription from Bergen consists of a nine-fold monogram of the runes q (þ) and n (n); yet another merely reads nnþnnþ. A monogram of nþr, presumably an abbreviated from n(au)ðr ‘need’ or an ideographic rune ‘need, ogre, ride’ (the name of the N-rune in the runic poems), is repeated eight times on another Bergen stick, alongside other magical symbols. The nine needs are a motif often invoked on runic amulets and later spells, something with which a spirit like an ogre or similar is cursed.

Some amulets are overtly Christian, nevertheless written in runes. Consider this text on a square box, which is extant in several variants; fragments have survived in several versions in Scandinavia and elsewhere:

“In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, amen. Cure!

May God’s five wounds be (my) medicine.

May my medicine be the holy cross and Christ’s passion.

He who moulded and washed me with holy blood,

expelled the fever which strove to torment me.”

Reducing remedies are also quite interesting, and not only these but charms in general can contain nonsensical formulae which may enhance the power of the spell. On a 12th century stick: Sator arepo teneth opera rotas. æekrær kreærman numen signum terram. æekrær kreærman numen signum terram. Consummatum est. Klas á. “Sator arepo tenet opera rotas. Acre, acre, ærnem, divine will, sign, world (repeated). It is done. Klaus owns (this).” The charm opens with the popular sator arepo magic square formula, found on several Scandinavian runic inscriptions - a translation may be “the sower Arepo? guides the wheels with skill”, more loosely “as you sow, so shall you reap”. It concludes with a mark of ownership, preceded by the Latin words of Christ as he died (one of many religious expressions typical of Scandinavian runic amulet inscriptions composed after the conversion). The stick also seems to record three unconnected words in Latin: numen ‘divine will’, signum ‘sign’ and terra ‘world’. Close parallels to this acræ ærcre ærnem / acre arcre arnem text are found in a variety of Old English manuscript charms (for staunching blood, against flying venom, against black ulcers, to make holy salve, etc.) and have been variously identified as containing Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic or Celtic words. The notion of a blood-staunching charm is perhaps supported in the runic version by “it is done”, the words uttered by the pierced and dying Christ on the cross. There are even inscriptions with the Cabalistic word AGLA (invocation ‘Thou art strong to eternity, Lord’), or encoded formulations such as Mistill, tistill, pistill, kistill, ristill, gistill, bistill; the “thistle mistletoe” formula betraying some pre-Christian origins.

Christian stories are alluded to in various runic charms. The names of the three men who escaped unscathed from the fiery furnace of King Nebuchadnezzar, for example, are found on two Norwegian runic amulets, one representing a charm for the eyes. “For the eyes. Tobias heals the eyes of this person. fa[i]faufao. Shadrach, Meshach and and Abednego (?). Salve (?) the eyes (?) ameos (?). For the blood.” There is a mix of old Norse and Latin, some decorative runes, and possibly some magic derived from Hebrew characters like fau, which in some mystical texts means life.

While such mysterious examples might strike us as fascinating pieces of cultural history, I think it is the casual doodles that need to catch our attention more often. Imagine sitting at a tavern in Bergen with your lads after a long day’s work, rain smashing the roof, wooden mugs clattering against rough-hewn tables, fishermen swapping stories of monstrous waves and near escapes, you there just holding your pint and waiting for the wandering musician to start his melody, when all of a sudden someone hands you a stick: Gyða segir at þú gakk heim – “Gyda says you have to go home.” She must have had a lot going on, too, yet you find yourself swearing and ordering another pint. Thorkell could write you that he sent the requested pepper. Sigurd could urge you to pay your debt. Arne could beg you to help him discharge some crops. Asmund could boast about having visited Rome.

These little moments reveal our shared humanity, centuries apart, yet so close.

References:

MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard. Runic Amulets and Magic Objects, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2006

Spurkland, Terje. Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, transl. by Betsy van der Hoek, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005

Database Runes and Ruins

Sator arepo (etc) is also from Latin. Nobody's sure today what 'arepo' means, if anything other than a word made up to make the magic square come out right.

I have a galdrastafr tattoo on my neck. I read about it in an old book (alas I am not sure where the book is). It is a bind rune. The story behind it was something like someone would put the five runes together - to bind them - on a pendant or other token to give to a someone else as a way of offering their love.