World of words - the beauty of Icelandic manuscripts

What Old Icelandic manuscripts looked like

The Edda building of the University of Iceland is the home of a small yet exciting exhibition containing wonders of national heritage: Old Norse manuscripts. For Norse and Viking geeks like myself, a truly spiritual experience. The exhibits change every couple of months, yet regardless of what is displayed, looking at these fragile yet enduring treasures gives you a sense of forlorn greatness : to produce such a manuscript would have been a colossal task.

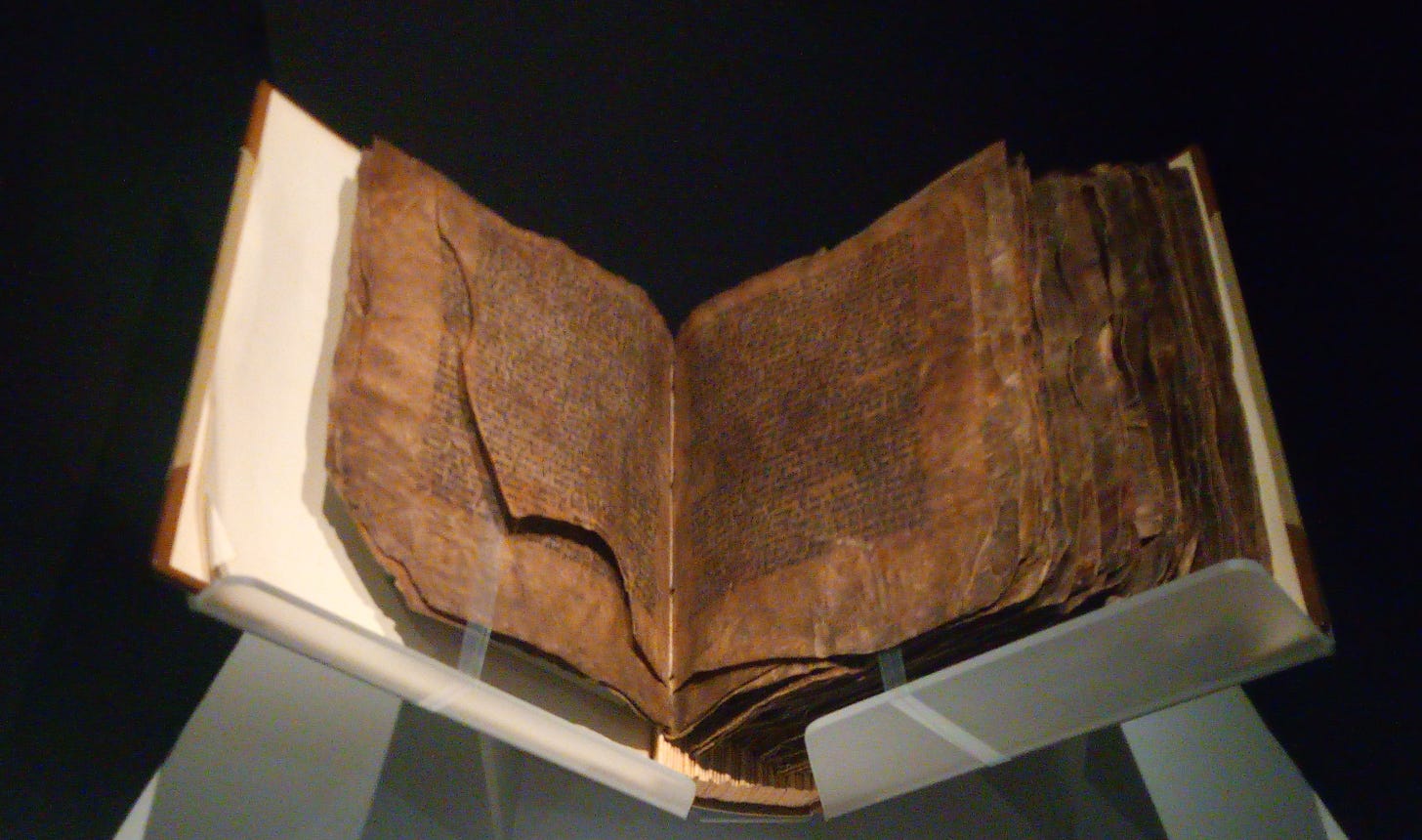

Above you can see the Codex Wormianus, one of the four manuscripts containing the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson, a handbook of poetics first and foremost, but also a “textbook” on Norse mythology as would have been preserved in the learnt culture of Christian Iceland. This amazing manuscript also contains The First Grammatical Treatise, written in the 12th century with the purpose of adapting the Latin alphabet to Icelandic needs. Sorry to disappoint, but Norse literature was not written in runes (there are indeed some runic codices from the 1300s but thez are rather revivalist and not a natural evolution from runic to Latin). This particular manuscript carries the name of a 17th century professor from Copenhagen, Ole Worm, and the reason why the pages appear much lighter than many other manuscripts is that they were washed in urine.

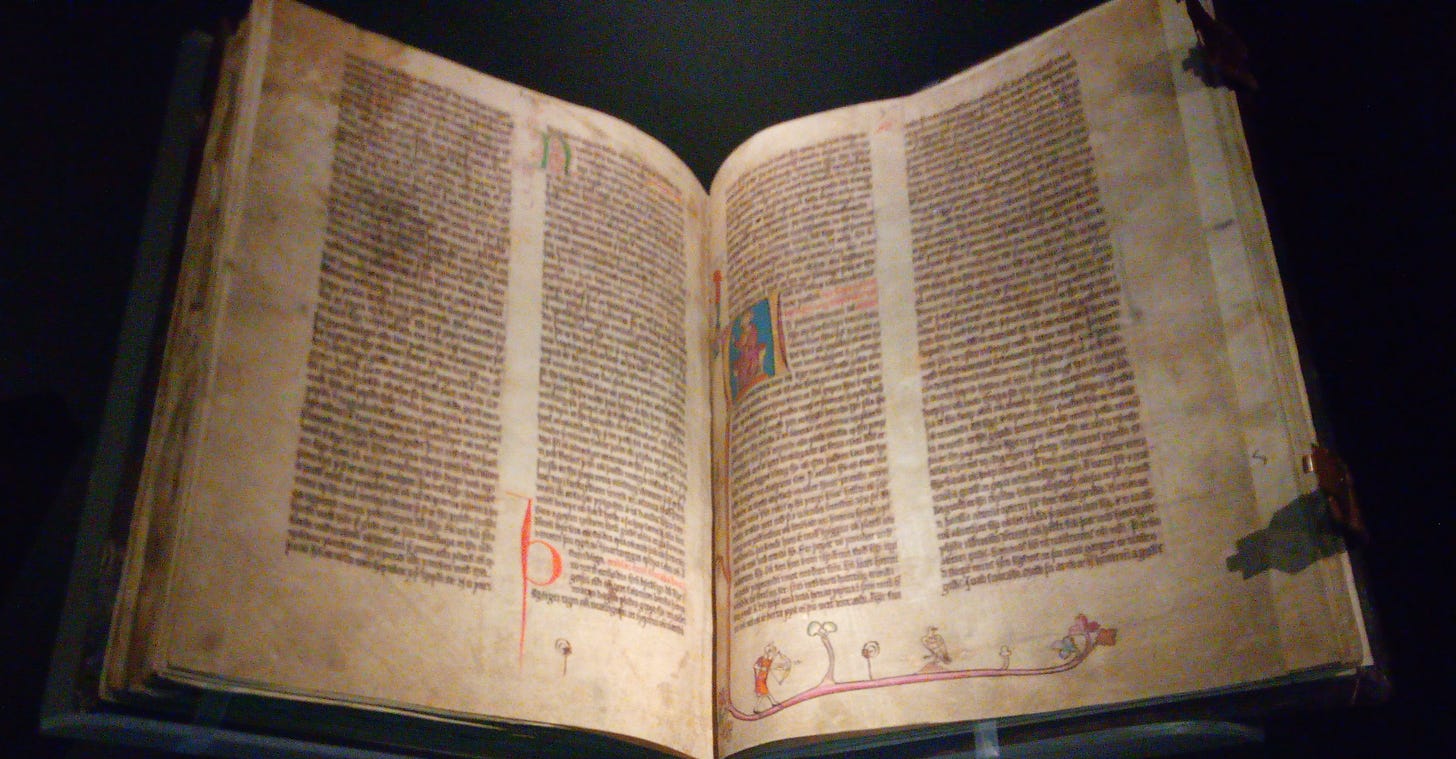

The image above is a manuscript containing marvelously illustrated Biblical tales. It probably originated in the Benedictine monastery of Thingeyrar in northern Iceland and includes tales of Old Testament translated into Old Norse with explanatory notes. Despite the poor quality of my pictures, I still hope you can appreciate the beauty of this creation written on light -coloured vellum and the rich illustrations. The initial letters are red, green, blue, with headings in bright red. Historiated initials depict scene from the Old Testament such as the Tree of Life with Adam and Eve or Abraham sacrificing his son. Pigments were brought from far away lands.

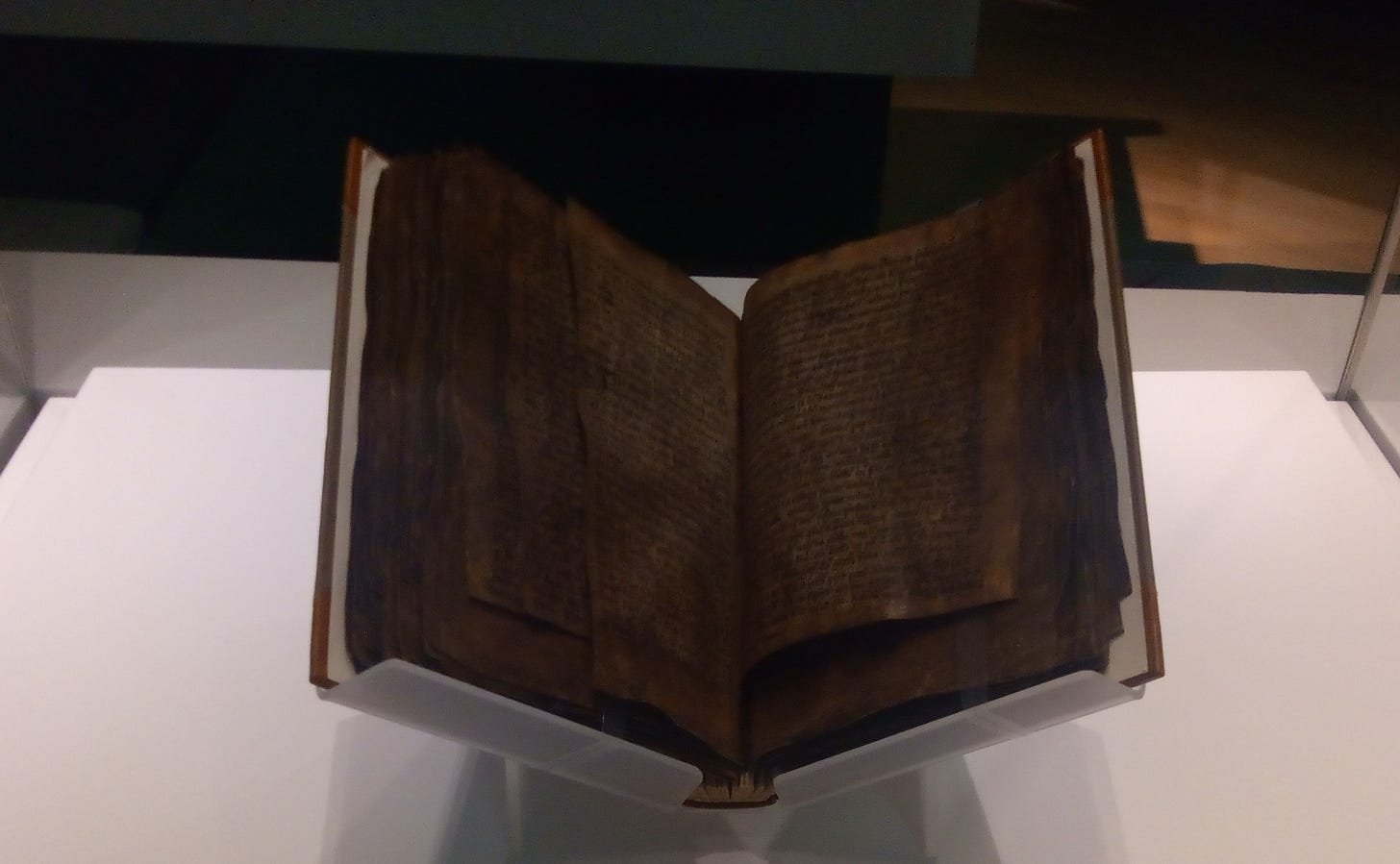

This one, occasionally known as Eggert’s book, contains stories of the famous outlaws Grettir, Gisli and Hördur. Interestingly, the saga of Grettir was followed by an erotic poem which has been erased by some prudish owner of the manuscript.

What you can see here is part of a “book of rimes a hand’s breath in thickness” as it was described in the 1728 collection of Árni Magnusson, later divided. Not all the pages are of the same size, but smaller sheets seem to have been deemed good enough. Perhaps the most fascinating part of the Staðarhólsbók are the scribbles inscribed on the margins by the visibly annoyed scribe: “my eyes ache”.

Did you know that none of the sagas are preserved in the original version by the hand who penned them? The sagas were disseminated by copying, so there are quite a lot of manuscripts of the different sagas, which sometimes even survive in several versions whose relationship to one another is not always that clear. Most of the oldest manuscripts are incomplete or just a few sheets. The oldest text seems to belong to the Saga of Egill Skallagrímsson (ca. 1250), however, the oldest Old Norse manuscript text would have been a religious charter from Reykholt, written about a century before.

“With laws shall our land be built, with lawlessness laid waste” - probably the most famous quote from the Saga of Brennu-Njál. What Icelanders in the Viking age actually implemented is hard to tell and rather inferred from the behaviour of saga characters. Parts of the bulky book, the Grey Goose law (Grágás) would have probably applied to some extent. The smallest book contains Krístinréttur, the Christian law of bishop Árni Thorlaksson, adopted in 1275. The youngest contains Jónsbok, approved in 1281 and remaining valid way into the 17th century, with amendments from the kings of Norway.

Other interesting examples I spotted were a sheet of music with a song for St John’s Day, a manuscript of astrology and palmistry intended to decode human nature in terms of the four elements and the fates of individuals in the stars, but also these 16th-17th century booklets serving as birthing aid. They all relate the legend of Margaret of Antioch, imprisoned for her faith and swallowed by a dragon - she managed to burst free after making the sign of the cross, an analogy for a successful birth. She prayed ever since for the health of children, which made such booklets popular with midwives.

I will surprisingly (sic!) end this short gallery with Norse myth. Long before Marvel, artists strived to depict Norse gods, goddesses and events from the Eddas. This wonder provides 16 full page images of Norse myth and stems from the creative mind of a poor farmer from eastern Iceland by the name of Jakon Sigurdsson (d. 1779). In a twist of fate echoing Viking voyages, Icelandic emigrants brought the manuscript to the New World, but the consul of Minnesota bought acquired it and fortuntely it ended up at the Árni Magnusson institute.

If I stirred up your curiosity with this short gallery, have a look at my YouTube channel where you can find plenty of material covering different aspects of the sagas and stay tuned for more Norse-isms on Substack!

Every time I read your posts, I feel spoiled by another world I can never know firsthand yet still so very much appreciate!

And once again, I must acknowledge that Iceland is a kind of Nerd Paradise--thanks for the reminder!