If you're a fan of ancient and medieval Scandinavian history, you NEED to know about this remarkable Icelandic treasure: the amazing manuscript called Flateyjarbók (Book of Flatey).

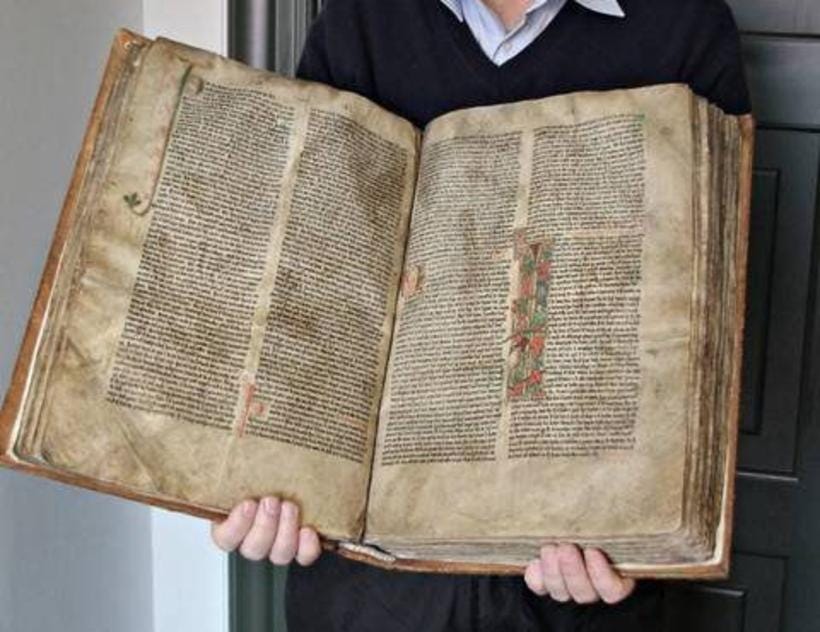

This extraordinary manuscript, formally known as GkS 1005 fol, is the largest of all surviving Icelandic parchment books. It consists of 202 pages written toward the end of the 14th century, with an additional 23 pages appended in the latter half of the 15th century. Today, it’s preserved in two volumes. But Flateyjarbók isn’t just exceptional in size; it’s also uniquely personal. While most Icelandic manuscripts of the Middle Ages remain silent about their origins, Flateyjarbók actually tells us who commissioned it, who wrote it, and even a little about when and where it was created.

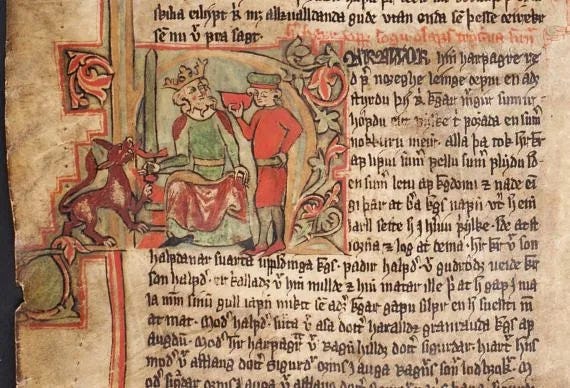

The manuscript’s preface proudly declares that it was owned by Jón Hákonarson, a wealthy farmer from Víðidalstunga in Húnavatn county (northwestern Iceland), and that it was written by two priests: Jón Þórðarson and Magnús Þórhallsson, with the latter also responsible for its illustrations. While we know little else about the scribes, the manuscript reveals that Magnús was still working on it up to seven years after the initial writing in 1387. After Jón Hákonarson’s death, the manuscript’s trail goes cold until it resurfaces in the possession of Þorleif Björnsson, a herdsman at Reykhólar, who likely added the 23 supplementary pages in the 15th century.

Ownership of the manuscript then passed to Þorleif’s grandson, Jón Björnsson of Flatey Island, who in turn passed it on to his own grandson, Jón Finnsson. It is thanks to this family that the manuscript received its now-famous name: Flateyjarbók, or "The Book of Flatey." In 1656, Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson convinced Jón Finnsson to part with it - not for his own benefit, but to present it as a gift to King Frederick III of Denmark. For three centuries, Flateyjarbók remained one of the crown jewels of the Royal Library in Copenhagen, until it was ceremonially returned to Iceland in 1971. The Danish Minister of Education, Helge Larsen, handed it over to his Icelandic counterpart, Gylfi Þ. Gíslason, with the simple yet now-famous words: “Vær så god! Flatøbogen.” There you go, the Book of Flatey.

Inside the book

The contents of Flateyjarbók are nothing short of extraordinary. At its heart, the manuscript is a grand compendium of sagas about Norwegian kings. Its two central sagas are the stories about the missionary kings Ólafs saga Tryggvasonar hinn mesta / The Greatest Saga of Olaf Tryggvason (d. 1000) and Ólafs saga Helga/ The Saga of Olaf the Saint (d. 1030), both of which are expanded beyond any other known versions. These are not standard retellings, they’re enhanced, embellished, and densely layered with supplementary texts and episodes. In Ólafs saga Tryggvasonar, for instance, the base text by Snorri Sturluson is enriched with additional material related to the king’s life and his Christian mission.

Many of the interpolated stories exist nowhere else. These include the Færeyinga saga (The Saga of the Faroe Islands) whose most complete and likely original version appears here, nearly the entirety of Orkneyinga saga (The Saga of Orkney Islands), parts of Fóstbræðra saga (The Saga of the Foster Brothers) not preserved elsewhere, and, most famously, the Grænlendinga saga (Greenland Saga) our only surviving source for one of the earliest narratives of Norse exploration in North America and the discovery of Vínland. The manuscript also contains a range of short tales (þættir) preserved nowhere else, including Einar Sokkason’s tale, Þorleif the Earl Poet, Þorstein Oxfoot, and The Tale of Hroi the Fool.

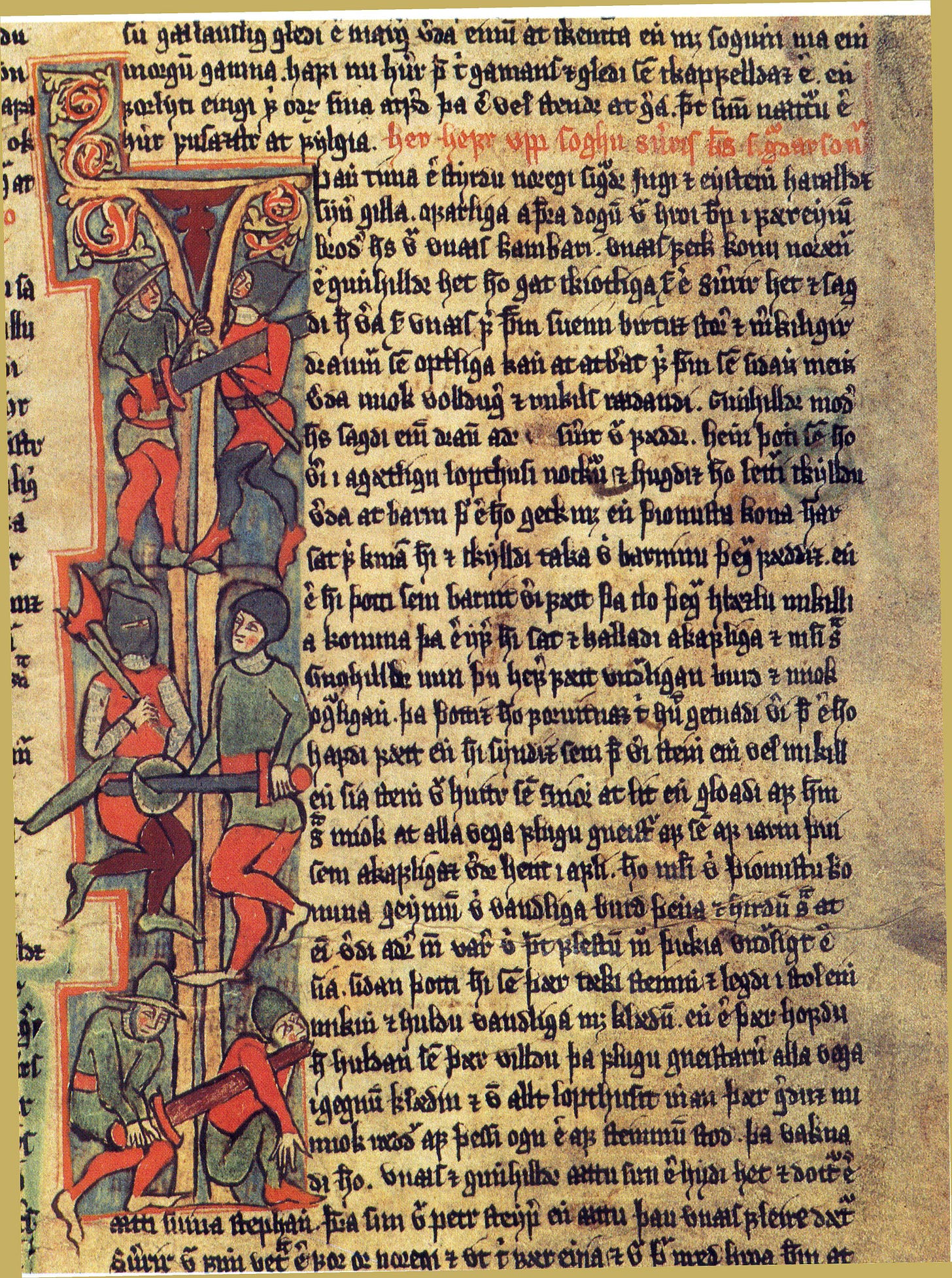

The second part of the manuscript continues with stories of later Norwegian kings, such as Sverrir Sigurðarson (d. 1202) and Hákon Hákonarson the Old (d. 1263). Sverris saga is the oldest known biography of a Norwegian monarch and was likely written by Karl Jónsson, abbot of Thingeyri (Icelandic Westfjords). The saga begins with an introduction attributed to King Sverrir himself and continues with accounts from his contemporaries. A church façade depicted in one historiated initial bears a striking resemblance to Thingeyri, suggesting it may have been the site of its production. Hákonar saga was composed by the renowned storyteller Sturla Þórðarson. Between the sagas of Saint Ólaf and King Sverrir, the manuscript offers a continuous chain of royal sagas. During the 15th-century additions, likely at the prompting of Thorleif Björnsson, the manuscript was further enriched with stories of other kings, including Magnús the Good and Harald harðráði (Hardrada, one of the blokes who claimed the throne of England in 1066), as well as Icelandic episodes tied to their reigns - all recorded on the 23 extra folios added at the end of the original compilation. At the very back of Flateyjarbók, there’s even a world chronicle that spans from Julius Caesar's rise as “dictator of the whole world” to the year 1394, a remarkable attempt to place Icelandic and Norwegian history within a broader, global framework.

What makes Flateyjarbók truly exceptional is not just the richness of its content, but its physical design. It is absolutely gorgeous. With its ornate illuminations and stylized initials, it is clear that this was no ordinary manuscript. It wasn’t meant for daily use by monks or scholars - it was a prestige object, meant to impress, to entertain, and to educate. It may well have been created as a luxury gift for the young King Olaf IV of Norway, who, fittingly, was named after Saint Olaf. Olaf was only sixteen when Jón Hákonarson initiated this ambitious project, and given that Jón’s grandfather Gizurr galli had once served at the Norwegian royal court, it wouldn’t be surprising if Jón aimed to emulate or even revive that legacy.

Some scholars speculate that the manuscript was originally intended to include only three sagas: Eiríks saga viðförla (Saga of Erik the Far-Travelled), Ólafs saga Tryggvasonar, and Ólafs saga helga. All three feature Christianisation as a key theme, highlighting the transition from paganism to Christianity in Norway. Thematically, they form a coherent narrative arc, with each protagonist - Eirík the Far-Traveller, Olaf Tryggvason, and Saint Olaf - playing a pivotal role in the Christian conversion of the North. This thematic unity suggests a deliberate design, even if the project later expanded. For instance, while Flateyjarbók does not include a separate saga of Harald Fairhair, the legendary first king of Norway, he is name-dropped at the beginning of Ólafs saga Tryggvasonar, linking the manuscript to the full arc of Norwegian royal history.

In a nutshell, Flateyjarbók is a cultural treasure of unparalleled importance. It preserves texts found nowhere else, many of which would have been lost forever without it. It even contains the only surviving version of the eddic poem Hyndluljóð (Song of Hyndla), which is now considered part of the Poetic Edda, the great collection of Norse mythological poems. More effort, artistry, and ambition went into creating Flateyjarbók than perhaps any other Icelandic manuscript. It was designed to be more than a book: it was, and remains, a literary monument. The manuscript has been digitised and can be found on handrit.is

Sorry if I missed it, but where is it kept? I am going to Iceland in early July and intend to visit the Edda Building at the University to see such items!

Love this! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com